Climate change poses a significant threat to numerous regions in the United States, rendering them increasingly uninhabitable due to rising sea levels, flooding, wildfires, and more. As a response to this challenge, managed retreat has emerged as a strategy to relocate affected households, neighborhoods, and even communities away from harm’s way. Although managed retreat can involve a number of processes, the use of buyouts––the voluntary purchasing of private properties using public funds (1) (which is intended to spur the relocation of at-risk households to lower risk locations), is a critical (and in many places, virtually the only) tool in a policy maker’s toolbox.

While physically moving people out of harm’s way makes intuitive sense, the real world applications of managed retreat-related buyouts are highly complex, emotional, and fraught with weighty fiscal and equity implications. Here we explore some basic financial considerations of managed retreat, shedding light on the challenges faced by affected municipalities and fundamental flaws in the system as a whole.

Financing Managed Retreat

“Managed retreat” (a term of art used by professionals in the field that many feel brings unnecessary negative connotations to a process that is already inherently difficult) refers to the voluntary relocation of households from areas susceptible to the impacts of climate change. To date, approximately 50,000 households have been relocated using buyouts throughout the U.S.; the proverbial “tip of the iceberg” compared to the number of such moves that will be necessitated in the future.

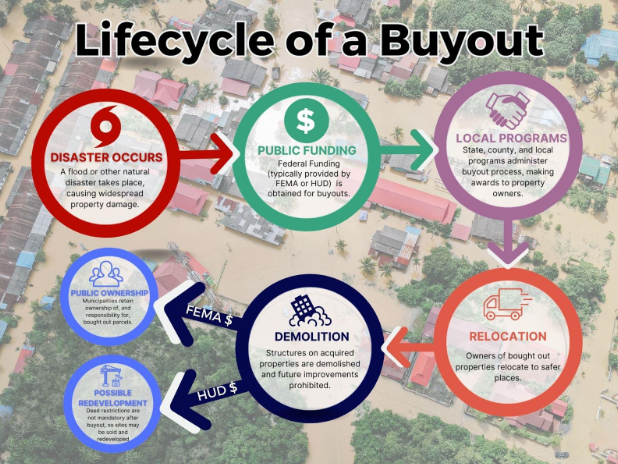

The programs that manage buyout logistics, working directly with local constituents and affected property owners, are implemented at the state and/or local levels. The funding for most buyouts, in contrast, originates at the federal level. Disaster relief dollars provided by the Federal Emergency Management Agency (FEMA) or Community Development Block Grant (CDBG) awards from the Department of Housing and Urban Development (HUD) are the most often used funding sources. Less frequently, other money may be put towards buyouts, including through the issuance of bonds by counties or other, more local levels of government.

However they are financed, buyouts are almost always voluntary and paid to individual property owners, who then use the funds to move, ideally to a safer location. Because buyouts are typically only made available in areas affected by climate-induced natural disasters, it is often the case that there are far more eligible parcels than money to buy out their owners. The dual realities of voluntary participation and limited funding run the risk of creating a post-buyout patchwork landscape of abandoned and inhabited sites, and can put program administrators in the undesirable position of choosing who to buyout and who to leave in place when there is greater demand than dollars.

Owners selected for buyouts are usually offered the assessed value of their properties pre-disaster. Sometimes the selling price includes an additional incentive, such as in areas of post-Super Storm Sandy New York, where participating property owners received assessed value + a 10% premium to incent participation. Often, however, pre-event assessed value is all that is paid, and participants must bear any associated costs of relocation, including realtor fees, mortgage registration fees, and travel costs themselves.

While the financial assistance available for these relocations is critical in moving people out of harm’s way, federal dollars are not provided to affected municipalities to support the long term costs associated with the care and maintenance of land that is left behind.

The Local Quandary

Upon purchase, properties vacated through buyouts revert to public ownership. Any structures present onsite are demolished, and in the case of FEMA funded purchases, legal limitations on future land uses––such as those prohibiting the construction of new structures or even improvements as modest as hardscaping to increase drainage, are permanently attached to the associated deeds.

What happens to abandoned parcels after they become public property varies widely. Some are allowed to go fallow, moving through the phases of ecological succession to whatever end state is naturally occurring for their particular location and topography. In the case of such loosely managed land, there is always the risk that it will become the site of illegal dumping or commandeered by locals for parking or other ‘unofficial’ uses. When such ‘organic’ site reuses are problematic, public officials may be forced to install fences, or in other ways take intervening actions to maintain the affected properties.

Local community members are sometimes involved in decision making related to abandoned site reuse, and preferences vary widely. Because buyouts are voluntary, not everyone to whom they are offered may accept, and in neighborhoods with more active associations of residents and a desire for a ‘cleaner’ aesthetic, manicured lawns are often the strongly desired end state for bought out parcels. Conversely, neighbors who have seen the effects of flooding firsthand may rally for abandoned sites to be altered to help prevent or lessen the next disaster, logical requests, but ones that come with often quite large price tags. Commemoration of pre-managed retreat land uses is also sometimes included in local land reuse strategies.

Whether allowed to go fallow or carefully maintained, local municipalities bear the responsibility and financial burden of these vacated parcels, essentially in perpetuity. Maintenance costs, coupled with the loss of ratables resulting from the property’s abandonment, therefore, represent a double fiscal whammy for the cities and towns where buyouts occur, and can serve as a disincentive for local officials to actively encourage managed retreat initiatives within their borders.

Unlike FEMA-supported buyouts, HUD funding does not carry the same requirements for restrictions on future land uses. This arguably stems from the fact that CBDG funds were not conceived as post-disaster support. However, by failing to require limitations on reuse, this funding mechanism creates the perverse possibility of public dollars being used to move one population of property owners out of harm’s way, only to have a new set of owners repopulate the area, thereby gaining exposure to all of the known climate change-related risk in the process.

At first blush, this outcome may appear to at least alleviate municipalities of the need to maintain bought out sites in perpetuity. This myopic view may be at the root of why such sites are sometimes allowed to be reused after coming under local government purview. In reality, cities and towns that permit redevelopment of these parcels may well be signing up for far greater future outlays when they are, for example, legally compelled to maintain roads to neighborhoods in which flood waters cause regular damage.

Clearly, neither FEMA nor HUD money offers a magic bullet for municipalities faced with the prospect of managed retreat. And some officials may further shy away from the process, not necessarily due to fiscal impacts directly related to the affected properties, but for fear of negative optics. If certain neighborhoods are abandoned because they are unsafe, the logic goes, residents and businesses in safer areas may receive the message that their city or town is becoming less viable, and therefore choose to relocate, even absent the immediate threat of climate-related disasters.

Because the buyout process is initiated and carried out at the local level, the possibility of myopic public finance concerns lessens the likelihood that buyouts will be offered is a real concern. Striking a balance between protecting residents and businesses, while still ensuring the continuing vitality of the community as a whole, is challenging. Ensuring that local decision makers have all of the information they need to make informed decisions and taking steps to curtail the negative local financial impacts of embracing managed retreat are critical to lessening risk in a changing climate.

Looking to the Future: Can We Build a Better Buyout?

An overview of current practices makes clear that while much has been accomplished in the field of managed retreat, significant work remains to be done, especially in the area of financing.

Currently, funding for buyouts moves in a linear fashion, from (largely) federal sources, to local authorities, to individual property owners. Nowhere in this equation are the private interests and industries, whose activities have so significantly contributed to climate change compelled (or even asked) to help offset the astronomical price tags associated with moving (what will ultimately be) vast swaths of the American population out of harm’s way.

This is more than just a missed opportunity. Pushing the fiscal burden of mitigating climate change risk wholly onto current and future taxpayers is ethically unsound. Better would be an approach in which constituents’ financial obligations were (at least somewhat) proportionate to their contribution to the underlying problem and ability to pay for the solution.

The current system is also almost guaranteed to fail at providing sufficient funds to support activities of the scale necessary. Indeed, in these relatively early days of managed retreat there are already waiting lists of homeowners in a number of locations who are hoping to be chosen to receive a buyout. Such situations put program administrators in the unenviable position of determining who should receive this form of (sometimes lifesaving) assistance.

Today’s version of managed retreat is also flawed in its creation of local disinvestments to participation. Whether affected jurisdictions are faced with the dual fiscal impacts of lost ratables and new site maintenance costs (as occurs with FEMA funding) or lost ratables coupled with the need to maintain infrastructure to support use of fundamentally unusable land, it’s a lose-lose scenario for local governments. Clearly, if our goal is to lessen people’s exposure to climate change risk we must create a system that encourages at-risk places to act in the interest of the people who call them home.

The key to engendering more engagement at the local level, it would seem, is to rewrite the rules of the buyout process to recognize that all land, even land that is unsuitable for residential development or other direct uses, has value. Climate change mitigation-based uses, such as engineering and planting to encourage storm water absorption and/or carbon sequestration seem like obvious options for creating value on abandoned parcels. Such land uses would not put human populations at risk, and would help combat the underlying process of climate change. They could also be made to have significant financial value, should the right policy instruments (such as a nationwide CO2 cap and trade program coupled with compulsory carbon offsets by major producers) be put in place to create and sustain that outcome.

Finally, the importance of education at the local level––for members of the public, but especially among local elected officials, about the likely effects of climate change within their specific communities cannot be overstated. From the homeowner deciding whether to accept a buyout, to the mayor and city council people balancing their populations’ safety against the future fiscal viability of their jurisdictions, to developers considering whether to rebuild on previously bought out land that’s been made available at a bargain basement price, an accurate understanding of the current risks, as well as future projections, is invaluable.

Conclusion

Given the realities of climate change, the importance of managed retreat and of buyouts as a key element of that effort will only increase over time. However, in order to accomplish relocations at the magnitude and scale that will be needed to keep Americans safe, we must rethink how we pay for these efforts and the financial realities we are creating for affected communities along the way.

Policies that close the loop between greenhouse gas producers and the costs of managed retreat, while recognizing and capturing the true value of land rendered uninhabitable, are key to the future success of the field. The creation of legal and regulatory structures to link these elements and facilitate the creation of ethically sound, sufficient and sustainable funding streams should be an immediate priority.

Note 1: The vast majority of buyouts are voluntary on the part of property owners, with a small handful of notable exceptions (see, for example, Harris County, TX).

Learn more and subscribe to our YouTube channel here!