It’s too easy for a northeastern US observer to have an overbearing and infuriating attitude regarding Mississippi. Unfortunately, Mississippi has a laundry list––or a butcher’s bill if you like, of past sins that stick in the craw of humanists and the respecters of justice alike.

That said, no one is innocent. Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. observed (after getting hit with a brick in Chicago), “As long as the struggle was down in Alabama and Mississippi, they could look afar and think about it and say how terrible people are. When they discovered brotherhood had to be a reality in Chicago and that brotherhood extended to next door, then those latent hostilities came out.”

So, we ought to look at the current problems in Jackson, Mississippi, bloodlessly and try to keep emotions out (I’m not saying it’s easy). What happens when a group surrenders political power but economic power remains the preserve of the privileged? Perhaps, it will turn out that political power is often no power at all. Instead, it takes politics and economics for political economy like two elements forming a chemical compound producing different behaviors.

Brute oppression, post-reconstruction, night riders, and finally, the freedom riders saw the long-promised political change. After Brown vs. the Board of Education and the Civil Rights Act of 1964, Mississippi changed forever. In some ways, at least. Since the 1930s, the state had become majority white as black Mississippians flooded north on Highway 61 and the Central Illinois Railroad to the cities of the urban North during the Great Migration.

2022: Year Zero Again

Yet, a very unfunny thing happened during this march for political freedom. Jackson desegregated its schools. Whites decamped to just over the city borders into the counties, and the white population decreased from 65% in 1960 to 35% today. Indeed, race can be a proxy for economic power. Businesses followed the middle class to the suburbs, meaning the banking system, the professions, and the “do-gooder class“ that often marked midsized American cities in the middle of the 20th century.

Jackson had been a city with good infrastructure, built to provide services to hold about 200,000 people. Instead, the population has dropped to 150,000, and those remaining don’t have the deep connections to the banking and business systems of the sort that encourage ongoing private investment. Often the first things that fall apart in a dis-invested city are the roads, sewers, and the water system. One need only look at cities like East St. Louis, Illinois, with a fifty-year jumpstart on a decline to see the inevitable dénouement.

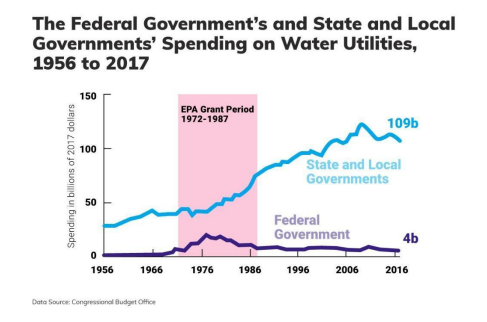

Jackson’s water system was holding its own until overall impoverishment led to fiscal corner-cutting that started about 20 years ago. The simultaneous annexation of Hinds County land into the city of Jackson proper expanded the footprint of the existing water system at the same time. These were the heady days when the federal government waded deeply into the guns and butter spending on Vietnam and the Great Society. When the 60s and 70s era of federal support ended (‘Okay guys, you’re on your own and good luck!’).

A Broken Tax System

Taxes are the price we pay for a civilized nation. How we pay those taxes, and in what form, may be debated, but it’s doubtful it’s a good-faith debate. Mississippi is a poster child for all this. A backward tax system pins down political freedom. The state sales tax is pretty high at 7%, and in one of the poorest states, they still tax groceries. And in Jackson, it’s pretty hard to find fresh food in decent markets.

Income tax has two rates: 4% and 5%. The lower rate kicks in at a generous dollar-a-year of wages, and the standard individual deduction is $2360.

The property tax system, which ought to be the backbone of a thriving community, is a disaster. If it seems designed by landholding grandees, then you’d be right.

Property valuation is a tiny percentage of actual value:

Single-family owner occupied, residential real property: 10%

All other real property, except real property in Class I or Class IV: 15%

Personal property, except motor vehicles and Class property: 15%

Public service property assessed by the state or county except for railroad and airline property: 30%

Motor vehicles: 30%

If you’re a homeowner, it seems like everything is fine. However, the homeownership rate in Jackson is just south of 50%. So the renters have to kick in more. And in a state with lousy public transportation, one’s car is assessed at 30% of market value.

Of course, being unable to pay for the upkeep of the water system is an issue across the country, from poor to middle-class communities. But, unfortunately, that’s also a curse on Jackson. The feds paid for a gold-plated water system, and nobody thought about the crucial issue of operations and maintenance (O & M).

The State

One would speculate that the Mississippi government would try to make Jackson, its state capital, a place of pride, but one would be wrong. For decades, all government-owned property was off the property tax rolls. Instead, the suburban-run legislature pinches each penny until it screams. Even a Hail Mary pass like the American Rescue Plan gave block grants to the state to divvy up amongst the cities, but the state led by Gov. Tate Reeve is putting conditions on the aid which no other city has to meet.

We don’t hear grumbling about other places where infrastructure is crumbling, failing, and falling apart (the power grid in Texas, anyone?).

O & M is the Crux of the Issue

Is it a good idea for 100-year-old pipes to feed the people their water? Probably not, but it makes sense to have a dedicated funding source to maintain a 100-year-old cast-iron line with proper maintenance. Maybe a municipal government sometimes does not make the right choices, but kicking control upstairs to the tender mercies of the Mississippi legislature and governor cannot end well.

We have to keep in mind that Jackson is just one of the hundreds of American communities with decaying water systems. Also, to step on sensitive ground, these systems were put in when a whole class of people knew how to build and maintain these things. This dangerous lack of skills makes it hard for a cash-strapped municipality to hold onto skilled workers; these workers can and do retire young because they’ve made enough money. Is it possible there’s more dignity in blogging from a co-working space in Portland? Possibly, but old-fashioned virtues like working for your family and helping the community still reside inside human hearts, so we have to make it cool again. Following Germany’s example, the American Rescue Plan would do long-term good by funding manual arts and sciences apprentice training. The youth of Jackson, Mississippi would be its best candidates.

The Mayor Works Hard

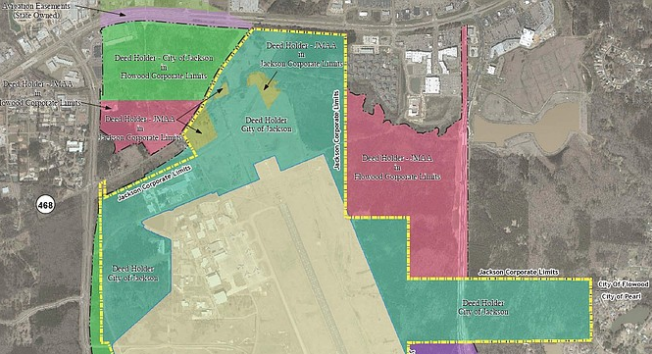

Mayor Chokwe Antar Lumumba of Jackson has been dealt a bad hand, like his post-1964 predecessors. Nevertheless, he wants to build a transformative city and deserves the resources to do so. Mayor Lumumba has been diplomatic about the state abrogating its responsibilities; nonetheless, more injustice is looming. For years suburban legislators surrounding Jackson have been trying to seize a precious public asset in the Medgar Evers International Airport. The usual arguments are trotted out: ‘Oh, the city is corrupt, oh, the city doesn’t have the brains to run it, oh, some of our pals want to buy the land.’

Since the airport is owned by and sits on the City of Jackson land, calling it a hostile takeover bid is not precisely a flight of the imagination. If we use history as a relentless guide, the issue is about land and control.

Take it away, Mayor Lumumba: “The same party that professes to be against eminent-domain takeovers has made the statement that we change the rules based on whom it favors,” he told the Jackson Free Press. “We don’t favor fairness; we don’t favor the rights of all; we favor the rights of our pockets.”

Everybody thought the right of property was sacrosanct. Maybe more sacrosanct for some.