Well, okay. Lots of people. One of the crowning strategies to rouse the rabble is to ream the property tax. Fair enough. But in some states like New Jersey, the property tax is unpopular, likely because the property tax is just as high as the state income, business, and sales taxes.

But some states have a lifeline for tax efficiency, equity, and progressivity. Yet because we live in strange times, state governments get the shakes regarding property tax. So instead, they throw themselves upon regressive, volatile, or inefficient taxes. Not surprisingly, these taxes hit parts of society that are powerless or don’t vote.

The property tax can trace its unpopularity to simple (and fixable) quirks in most states: the bill comes due once a year. There are legitimate concerns over what happens to people on a fixed income. The house’s value may go up, but there’s no cash flow to pay for a tax bill that goes up.

Solution 1: The government spreads the property tax bill over a year. In other words, pay it just as you do with a mortgage. The sticker shock comes when one is in a paid-off house, and suddenly, you have to write a check to the government instead of a mortgage company.

People with mortgages (Millennials, Gen X, and to a more minor degree, Baby Boomers) probably don’t know their property tax. It’s all part of that zany package called modern American housing finance.

Solution 2: Homeowners, usually seniors, may have an issue paying their property taxes. But that issue is ripe for exploitation, with the tried-and-true appeal to the heart of the “poor widow.” The spiral of the California real estate market has been tracked to the widow-pleasing Prop 13. Meanwhile, workers and young families live an evanescent, vagabond life.

In practice, many selected groups (military veterans, disabled individuals, etc.) enjoy property tax exemptions. The same objective, but more robust, is a property tax deferral.

A total exemption might be out of the question (governments love that tax revenue!), but a deferral achieves just that. In addition, most state constitutions are loose enough for a deferral program.

How Does Deferral Work?

The state legislature passes a property tax deferral bill; naturally, everybody shows up at the bill signing behind the governor’s desk. It’s signed, and the Tax Department figures it out.

Idaho is an excellent example of the mechanics of deferral. The applicant has to meet one of many conditions (disabled, widowed, over 65, disabled war veteran, etc.). The applicant’s annual income must be under a set amount (in Idaho, of around $50,000. The deferral turns into a lien on the property with interest. More attractive would be an interest-free lien, but that’s just our bleeding hearts talking.

There, all fixed! Now:

Toward a State Property Tax

In the past 20 years, statewide property taxes have popped up to address the fundamental differences in the economies of various towns because most state constitutions require education for all with no favor. It’s an elegant solution to the tsunami of lawsuits filed by education funding advocates who claim that poor school districts can’t provide sufficient funding for their schools.

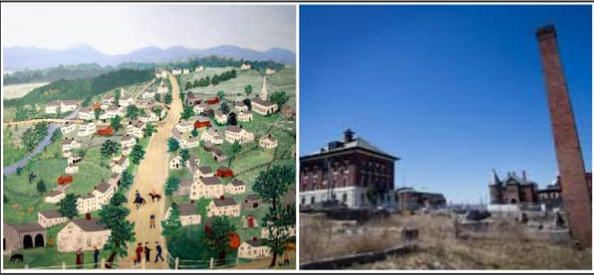

Another case study: Vermont. Contrary to popular belief, Vermont is not just a more extensive and leafier Upper East Side. It has pockets of incredible wealth bolstered by vacation homes, ski resort areas, (and refugees from the Upper East Side). But Vermont also has desperately poor pockets of both rural and urban poverty. By pooling property tax from all local jurisdictions, the Grandma Moses pretty towns pay more than the hardscrabble ones. As a result, all Vermonters benefit now (to keep the youth strong & moving in the right direction) and later (they grow up to be taxpayers, sharing the burden equitably). The American ideal of an even playing field bears fruit.

New Hampshire does the same, except the amount raised is defined in the law, so it’s not adjusted for inflation.

An Old Dominion State Property Tax: Let's Put Vermont to the Test in Virginia

A state property tax can only work if there is an agreement (or trust) that similar properties are valued similarly to other such properties. Then, the state board can determine the Variations expected among the different locales. This is the principle of equalization (a valuable step-by-step explanation comes from Oswego County, New York).

Since this example will be the state of Virginia, would a downtown storefront in Galax be valued differently from one in downtown Alexandria? Of course. Notwithstanding the differences in the buildings, the differences in site value would be enormous. So the task is to find current market conditions from town to town and county to county. (Editor’s note: the Galax Smokehouse is priceless in our eyes.)

Especially if reform comes in the shape of a state property tax, the variables must be accounted for accurately. It’s hard to do, but all good things in life are.

In Virginia, the boards of equalization are a county (or a city) affair. Sales figures are collected by the Virginia Department of Taxation annually to compute aid to local education. The tax department then calculates the ratio of assessed values to actual sales. These ratios are sent to a room with other financial reports) and collated into spreadsheets.

A Stable Revenue Source

Like clockwork, most governments in the US panic when revenues start collapsing like a cheese soufflé. In recessionary times, tax receipts fail in this order: income taxes, sales taxes, general business taxes, and property taxes. That makes sense: job loss leads to lower revenues. The unemployed can’t buy things that they usually would. Businesses starved of customers with cash go belly up or suffer.

The stability of the property tax in hard times is noted by scholars continually. After the Great Recession of 2008, census data indicated that counties with more robust property taxes not only revenues flowing but also recovered more quickly from unemployment. The Covid recession of 2020 revealed that transactional tax revenue cratered while property tax stayed sprightly. Foreclosures were rare as governments preserved the status quo during the emergency. Additionally, for renters, evictions and utility shutoffs were suspended for the duration.

It takes vision and imagination to decide whether to forgo or reduce a tax. So, it should be done slowly, like most ideas that affect the economy. Yet, the sustained pattern of revenues during a recession ought to be a wake-up call. Is it possible? So, let’s look at the numbers.

State aid to schools is around $8 ½ billion dollars. That revenue comes from the general fund, sales tax receipts, the lottery, and other sources. Suppose we collect the taxable value of land in Virginia. We can transfer that needed revenue from inefficient and unreliable taxes to a stable source: land.

The effect is immediately progressive: Northern Virginia possesses a wealth almost beyond measure. Since most of that wealth comes from taxpayers across the United States, who can begrudge a few dollars to the poor and dispossessed of Virginia? Alexandria, home to cute and fabulous streets (not to mention NCIS), is geographically analogous to Galax (14.9 mi.² to 8.2 mi.²). A 2% annual tax on taxable

land values would pay Alexandria’s contribution to the Virginia community at $606 million. Galax, far away and waiting for the future, would contribute $1.8 million a year. Both communities would be contributing a manageable amount, given their situations. All would become stakeholders.

Along with a few other NoVa communities, these locales could assist poor urban and rural communities straining to pay for education and patch holes in the roofs. This assistance would forge a stronger Virginia in its children and economy. Virginia communities, cities, and counties would contribute at least $8.5 billion annually to a statewide LVT. Time for a blue-ribbon panel tax commission?