As academics, advocates, and pundits scramble to explain the rising burden of housing costs in American cities, much has been written about the specter of vacant housing. A symptom of wealthy speculators, vacant units indicate that many investors are happy to park their wealth in real estate and profit from growth in land values without the hassle of actually having to build or rent-out empty units. This narrative is often paired with calls for a tax on vacant units, which is expected to push these units into being made available for use by tenants. While there are merits to this argument, it misses the forest for the trees, as it entirely fails to identify and fix two other ways in which scarce space within our cities is wasted: through vacant and/or underutilized urban land. Just like vacant dwellings, vacant and utilized lots are held out of use by speculators when they could instead be housing many more people.

In this article, we will summarize the existing research on the causes and consequences of urban land, which primarily centers on the existence of blighted land in struggling cities. We will argue that vacant land is also a problem in more successful cities, due to what we’ve labeled as speculative vacancy. We will describe our own research into speculative vacancy in New York City (NYC), before suggesting some policy responses that can discourage wasteful vacancy on our most valuable land, ultimately increasing the supply of housing and creating more thriving cities. We will extend these themes to discuss speculative underutilization of urban land in a later blog piece.

Previous research into vacant urban land has primarily focused on the concepts of blight and urban decline: an area loses its competitive edge, employers and workers move away, buildings fall out of use, and land ultimately becomes abandoned. This story is present in discussions of suburbanization, abandonment of old industrial neighborhoods, and the general decline of old manufacturing powerhouses like Detroit. This type of vacancy produces many well-documented harms: health hazards, infestations, trash, poor ecology, heightened levels of crime, and general economic decline. Vacancy can trigger a vicious cycle of neighborhood decline, as abandonment of one location lowers the value of neighboring properties, eroding the local tax base, undermining public investment in the area, leading to even more vacancy nearby. As one study put it, “an excess of empty urban lots can disconnect the local community, generate unsafe conditions, lower the quality of life, produce unsightly aesthetic consequences, blight surrounding areas, deter future development, and decrease economic growth.”

However, vacant land is not just an issue for cities suffering from decline. Many cities on an upward trajectory continue to feature pockets of land that remain stubbornly vacant even while the city thrives around them. For example, NYC has largely continued to thrive since the drop in crime rates during the 1990s, with the city now being so desirable that median rent in Manhattan topped $4,000 in July, for the first time ever. Despite such high demand for access to NYC, around 4% of all land across the city remains vacant, around one third of which is wholly unused. This draws our attention to a different type of vacancy, which we refer to as speculative vacancy.

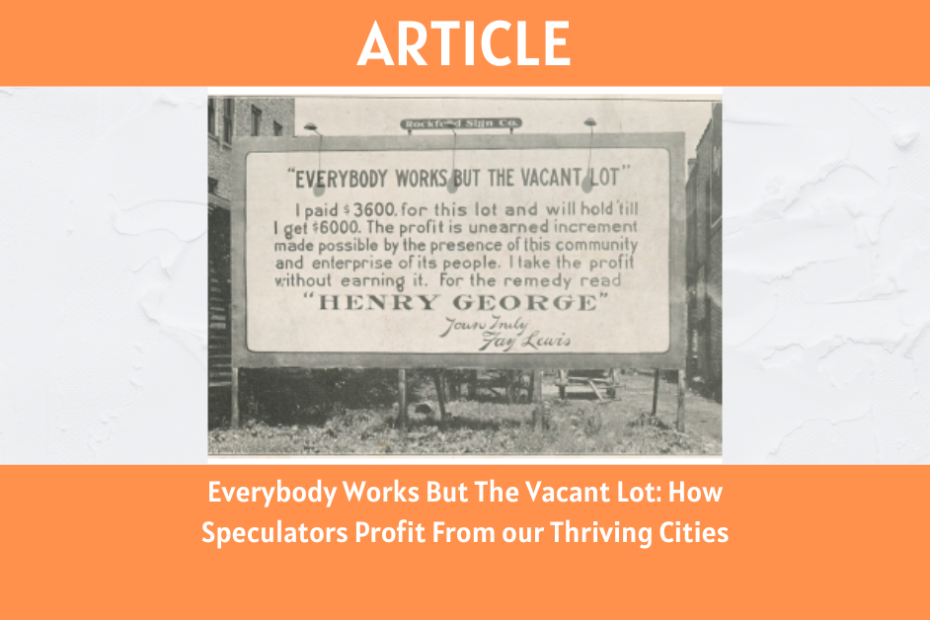

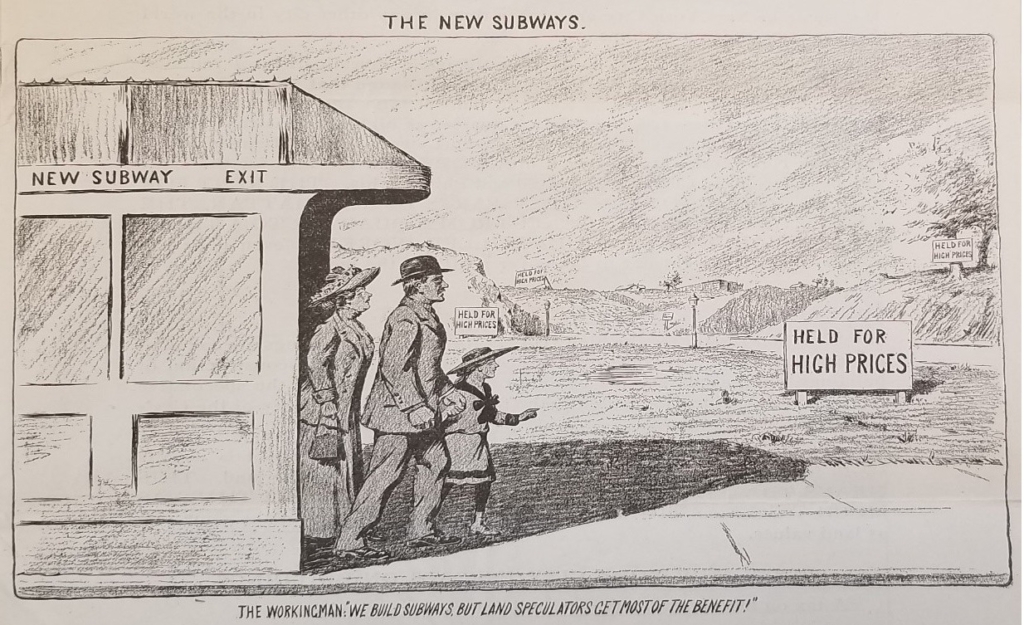

Commonly called ‘land banking,’ this type of vacancy involves investors purchasing land and waiting for land values to rise before selling the property and making off with their unearned profits. Often they will spend time in the interim lobbying for favorable changes to public policy (for example through relaxations of land use regulations) or public investments that will benefit their property, such as transportation infrastructure. The lessons of Henry George help to explain the presence of speculative vacancy: the inherently-fixed supply of land at a given location ensures that increases in a city’s population, productivity or popularity will inherently embed into higher land values, ensuring that landowners will enjoy the benefits of an advancing society, regardless of whether they put their land to work.

One study exposed this type of speculative vacancy, showing that 25% of downtown Phoenix was held vacant or used for surface car parking, right through the booming 2000s. During the years before the global financial crisis, there was a rapid rise in speculative transactions of these vacant properties, with the average land price rising in value by 10 times between 1992 and 2012. Many of the parties to these transactions were LLCs; we will examine the intersection between speculative vacancy and LLC ownership in a subsequent article.

Standard models from urban economics can help explain these patterns of speculative vacancy. Landowners decide to develop their property at the moment in time at which expected future profits are maximized, given the trade-off between the opportunity cost of holding land vacant, the costs of development, and the floorspace rents that can be earned once the site is developed (for an example see Razak et al., 2018). Where residential rents are anticipated to continue rising, landowners may prefer to hold their property vacant while waiting for that optimal moment to arrive, and enjoying increases in the value of their vacant land in the interim. Such behavior can result in persistent vacancy even in the midst of sky-high housing costs.

Speculative vacancy produces additional types of harm over and above those previously discussed. Due to the “emplaced nature of being,” humans have no choice but to use land in all aspects of social and economic life. If land in our most productive and desired cities is being left vacant for long stretches of time, that makes us all worse off. It also forces us to occupy second-best locations that require longer travel times and are less productive. By delaying the provision of urgently-needed housing to markets starved of supply, speculation contributes to exorbitant housing costs. And where property taxes are charged on both land and buildings, vacancy enables landowners to pay fewer taxes, rewarding speculators while requiring higher taxes be paid by the owners of buildings, businesses and homes.

While speculation on commodities can oftentimes produce social value, for example by increasing liquidity and helping producers hedge against risk, these benefits do not exist for land speculation. Land at a given location is geographically unique, meaning that supply cannot be expanded in response to speculation bidding up prices. This makes land a poor hedge against volatility, and indeed plays a central role in the business cycle, another relationship identified by Henry George more than a century ago.

Here at the Center for Property Reform have been analyzing the factors associated with speculative vacancy in NYC, using more than 840,000 tax lots in the MapPLUTO database. We classified more than 18,000 lots as being entirely vacant, equal to 2.2% of all properties in NYC. The map below highlights the locations of currently vacant lots. Significant clusters of vacancy can be seen in Bed-Stuy, in the industrial areas of Maspeth, in Jamaica, and both Hunts and Clason Points in The Bronx. Even in Midtown Manhattan, clusters of vacant land can be observed amidst some of the most valuable real estate in the world.

We found some indications of vacancy in blighted neighborhoods, with vacant lots being more common in Staten Island and the Bronx, neighborhoods with lower rates of employment and higher rates of SNAP usage, and in neighborhoods with more people of color. However, there were also some indications of land banking, with lots being more likely to be vacant if they were closer to a subway station or if they had been rezoned within the past ten years.

One striking example of the profits that can be made from speculative vacancy is the block of land at 514 Eleventh Avenue, between 40th and 41st Streets. Formerly the site of an old Mercedes dealership, this building was acquired for $100m by an LLC representing Larry Silverstein in 2015 and the buildings immediately demolished. Since then it has sat entirely vacant, and although several developments have been proposed, no construction has come to fruition. Two whole acres of land are being wasted right in the heart of one of the most expensive real estate markets in the world. And all the time that this site is left vacant, it continues to rise in value. If the value of this site has risen at the same rate as the Case-Shiller Index for New York, it will be worth at least $53m more than it was worth in 2015. One reason why Silverstein may be in so little rush to develop this site is that it currently has an assessed value of only $21m, roughly one-fifth of what it was worth in 2015. Property taxes are therefore incredibly cheap relative to the actual value of the property, providing very little downside for delaying development until a later date.

So what can be done about speculation on vacant land in our thriving cities? The first step is drawing attention to just how much land is going vacant year after year. While HPD reports annually on the presence of vacant units and on city-owned vacant sites that are suitable for affordable housing development, such reporting should be expanded to include a regular count of privately-held lands that are suitable for development, including for affordable housing. Our map of NYC Vacant Land can help inform New Yorkers of the presence of empty lots in their neighborhoods.

Property tax reform is essential to discourage speculative vacancy. Unfortunately, the City’s recent Advisory Committee on Property Tax Reform did not address vacant land at all, focusing instead on property tax exemptions for owner-occupiers, no solace at all to the City’s many tenants. Any tax reform will be utterly incomplete without raising tax rates on vacant lots. Here at CPTR, we have also long advocated for NYC to create a new property tax category for vacant land, called Class 5. Parcels within this class would be taxed at their full and fair market value, rather than enjoying fractional assessments that only tax a fraction of their value. Mirroring calls for a tax on vacant units, such a policy would be equivalent to a tax on vacant land. By increasing the annual cost for holding vacant land, this tax would encourage property owners to develop their sites more rapidly, or otherwise compensate society for wasting our most precious natural resource. Alternatively, the City could make a revenue-neutral tax shift, raising mill rates on assessed land values, and cutting taxes on buildings. Finally, forms of value capture, like a tax that captures the windfall gains when a property is upzoned, can discourage investors from engaging in land speculation and ensure that their profits come from actually putting their properties into productive use.

Next time you wander past a piece of vacant land in your city, contemplate the many ways in which it could be used to benefit the community, and the speculative profits the landowner might be enjoying in their sleep.