Along with New York City, Newark, New Jersey, possesses one of the best locational advantages of any city in the United States. Founded in 1666 by Connecticut Puritans, the town grew by leaps and bounds; the Industrial Revolution sparked a meteoric increase in population and a multi-sector industrial and commercial base. First, canals and then railroads converged into the city. With a population of 8000 in 1820, people poured in, swelling the city’s population to 367,000 by 1910.

The civic confidence of Newark was such that city leaders in government and business thought it was time to go big. In the era of bold public development, the Meadowlands of New Jersey (known as Newark Meadows) consisted of 46 square miles of what today we would call wetlands but then were called “wastelands.” 4300 acres lay inside the city limits of Newark, and plans were executed and funded by the city to build a port from the “reclaimed” land.

It takes a certain creative imagination in the 2020s to think that a city (not the state, not the Feds, and certainly not a stumblebum Port Authority) pulled this off by issuing bonds and bouncing the property tax rate up a bit.

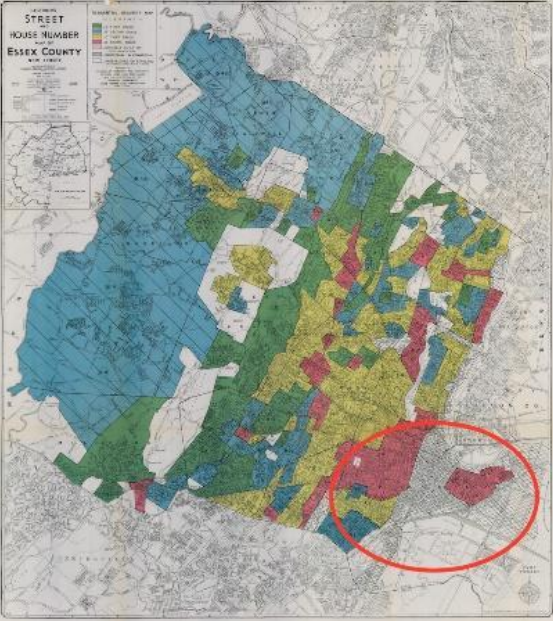

The last 100 years have been hard on Newark. The Great Depression of the 1930s was a challenge for industry and shipping. Already the bourgeoisie was starting to decamp to surrounding township and boroughs. Population declined from a high of 442,000 in 1930 to 270,000 in 1980; happily, that trajectory has reversed itself. Redlining discouraged both diversity and neighborhood improvement. The Federal housing administration’s loan programs consciously promoted race and economic segregation the effects of which still hurt cities like Newark today.

The end of World War II saw the advent of the G.I. Bill of Rights with its massive program of home loans financed through the Veterans Administration (but administered by the banking system). Yet, most of these home long programs serviced only the suburban vision of the single-family American home. Newark’s established infrastructure and building patterns were not quite “right” for low-interest or subsidized loans.

Further complicating the economic picture was the backlash of the population against the police brutality case in 1967, leading to confrontations and violence. Property damage was extensive and essentially ruined neighborhood economies. Absentee owners bailed and black-owned properties lost value. The effects of this ruin are omnipresent today.

What is Wrong with Absenteeism?

Absentee property owners are not necessarily a problem. For example, the tippy top skyscraper condominium is a bright shiny thing but not necessarily owned by anyone in town. Same with industrial and other commercial properties. When we move into the residential sector, however, that’s where the problems can start.

Some cities try to tackle absenteeism by shaming or bribing because municipal government is too-often disempowered by the legal system to timely seize and turn over a parcel. Not many cities are like Boston, which has a rigorous program intended to hunt down and nail absentees.

Homegrown Homeowners

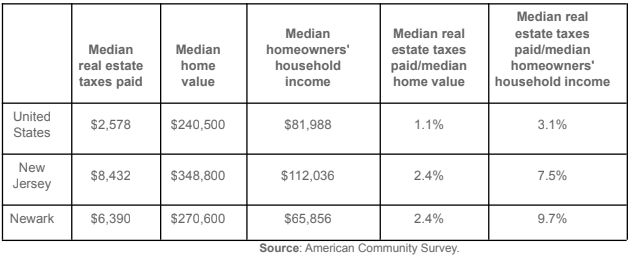

Newark is a city that does not own itself, in the nearly literal sense. Homeownership is abysmally low at 22%, a startling number by any measure (statewide ownership rate: 63%; nationwide ownership rate: 65%). In fact, Newark’s ownership rate is the lowest of all mid-sized cities, according to the good folks at Roofstock. Of the 29,700 residential parcels, 6,890 have zip codes outside of Newark. 9.7% of all taxable parcels are vacant (we can assume absentee status). Do taxes stymie homeownership in a poor city? Yes, of course. In a city where prospective homebuyers are already cost burdened and affected by low incomes, Newark has a force-multiplier created by New Jersey’s notoriously high property taxes.

Tax Abatements Reconsidered

Newark has no problem in attracting big projects. This is because of New Jersey’s very generous system of tax abatements. For example, the old Metropolitan building just scored an abatement for 25 years.

This should raise the eyebrows of most citizens. An abatement this long will never benefit the community. Think about the depreciation schedules offered by the IRS. The top range of depreciation is 39 years (land value is prohibited from depreciating).

For that matter, there is no legal requirement that the local school districts get any of the payment in lieu of taxes the program provides. In-depth examination of the abatement program does not exist, although the New Jersey state comptroller’s report from 2010 highlights some of the problems (including cronyism and “let’s sweeten the deal” syndrome).

But What About Hard Work and Investment Capital?

There was a time in America when if you wanted to throw up a building you didn’t go scrounging for tax breaks. You secured the site, you secured the lending, you hired workers and presto, a building. In the city of Newark, such audacity would be met with punishing property tax bills. So, the logical recourse is to do nothing and sit on the land or have the taxpayers of an extremely poor city foot the bill.

The conclusion by most studies show that a tax abatement, no matter how well-intentioned, will end up costing the city revenue. But the city will not pay that difference, property taxpayers will. And the homeowners will continue to have high property taxes.

The LVT Alternative

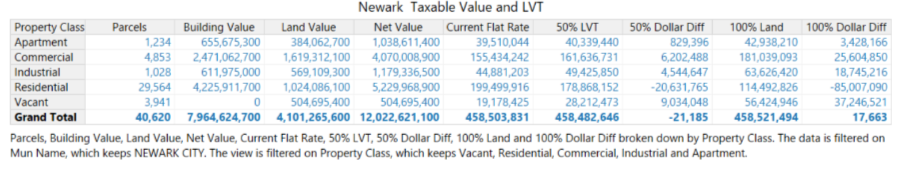

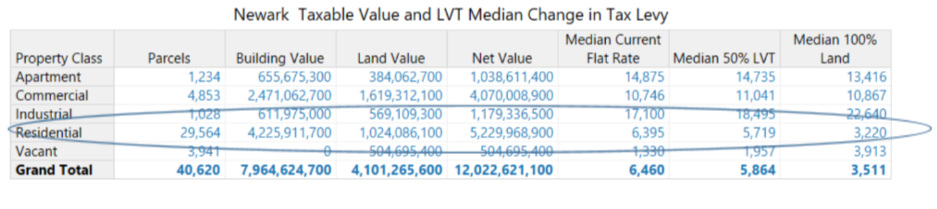

The land value tax does not demand that tax breaks and abatements end. But LVT does provide a way to soften the hit on residential properties and still gains revenue from land, including abated land. In a possible scenario, if Newark lessened its dependence on building revenue (currently 66% for the city and 88% for residential) and split the revenue percentages to 50% land and buildings, the benefit for long-suffering taxpayers is clear: revenue neutral outcome is achieved residential sees a significant reduction in taxes. Extending the scenario, 100% of Newark’s revenue from land value would cut residential taxes from the current $200 million to $115 million.

Expressing those numbers in median changes per property for residential (and to a lesser degree apartments and commercial) would see fiscally noticeable changes in tax bills.

For decades, Newark has been struggling to regain its former greatness in the face of harsh economic and social change. The property tax has to pay for things, but it doesn’t have to make the most vulnerable pay for it. All told, just over 70% of taxable properties would see a tax reduction in Newark. It’s time for some good news for the Brick City.